Observations

1. Observations of the Edgeworth Kuiper belt

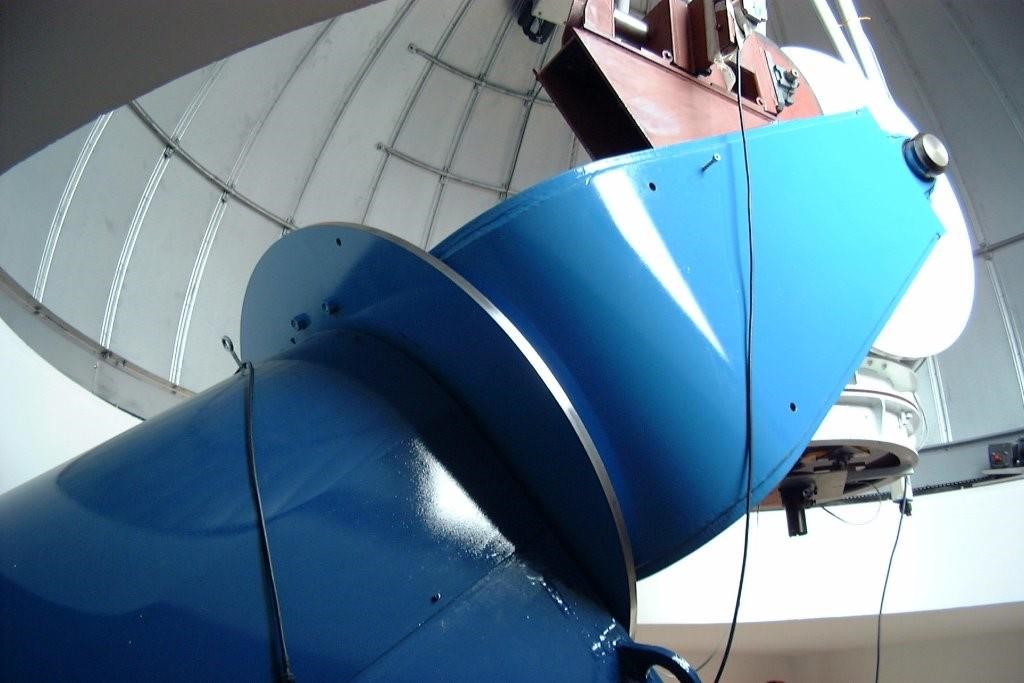

Kingsland Observatory carried out a survey in search of highly-inclined Edgeworth Kuiper belt objects (EKBOs). The objective was to investigate the size distribution and inclination distribution of high ecliptic EKBOs using a detected sample drawn from a well-characterised instrument using the 0.9m telescope. This involved a dedicated search of high ecliptic latitudes accessible from Kingsland Observatory over a four-year period. The search included 5530 star fields, covering a total sky area of 277 deg2. Ninety-two percent of the observations were carried out at inclinations >4° from the ecliptic. The survey resulted in five EKBO detections with radii from 138 to 600 km, and inclinations from 10.2° to 35°. Monte Carlo simulations were used in this analysis and applied an exponential distribution model with radius distribution power q, with q ranging from 3.0 to 4.9.and a Gaussian inclination distribution with FWHM ranging from 20° to 60°. The Monte Carlo statistical analysis indicates that the parameters used by previous authors for modelling their Classical EKBO observations do not fit the actual survey result of five detections at high ecliptic latitudes within a 3-sigma confidence level.

2. Survey for detecting a large planet in the outer Solar System

The presence of an unknown distant giant planet in the Solar System has been postulated to explain apparent clustering either of the arrival epochs or aphelion directions of long-period comets in a number of studies, but so far no planet X has been detected. One such study resulted a list of candidate objects found from a search on archived UK Schmidt sky survey plates. The results from that search to determine if any of the candidate targets exhibited planetary characteristics was followed up with a 4 year survey. The follow up search for the ‘Planet’ candidates was carried out over four years using the 0.9m telescope at Kingsland Observatory to 22.7 Sloan i band magnitude when using deconvolution image processing. These observations were performed in September and April in order to detect any parallax of a distant object. No astrometric shift was found with any of the target ‘Planet’ candidates. This suggested that 1) the original SuperCOSMOS digital images were always seen with artefacts which created the illusion that the suspects had the characteristics of a slight shift; or 2) the suspects were faint stars at or beyond the original plates’ limit of resolution. The fact that a planet X in our Solar System has not yet been found does not prove it is not there. The future still holds the possibility of finding a planet. The Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) is the best hope at present for performing a search for a distant companion to the Sun with a spatial resolution of 2 arc secs with it’s long thermal emission to constrain temperature. However, motion detection will come from GAIA in the near future. Wider constraints for combinations of mass and separation may have to be applied in order for a solar companion to be discovered.

3. Observations of EKBOs by occultation

Searching for EKBOs at high ecliptic latitudes was one of the goals of the previous survey. The limiting magnitude of 22 of the survey determined a focus on bodies exceeding radius 30 km. At the ecliptic, pencil-beam searches have detected EKBOs as small as ~5 km radius supporting the theory of collisional erosion effects in the ecliptic region of the EK belt producing a considerable number of smaller bodies. Small bodies in the ecliptic region of the Edgeworth Kuiper belt make up the majority of previous survey discoveries. There are presently limitations in the ability of existing large ground based direct imaging telescopes: they cannot achieve detections of faint >30 mag bodies in the outer Solar System needed to detect sub-kilometre sized bodies. Stellar occultations are a useful methodology for detecting otherwise undetectable faint objects in the outer Solar System. As the smallest EKBOs are the most numerous among those known in the ecliptic region so far, if this size distribution is correct the more numerous the small EKBOs, the higher the occultation rate should be.

A development by Space Exploration Ltd of dual band high speed photometry offered the potential to detect small objects within the Kuiper Belt during stellar occultation events. This innovative two-colour photometer, based on simultaneous observations with two EMCCDs has the potential of detecting sub-kilometre EKBOs with the 0.9m telescope when used in conjunction with appropriate analytical software. Preliminary tests confirmed that the system operates as designed, and that it is possible to see differing dip profiles in the blue and red wavelengths when observing a known EKBO occultation event. The optimal conditions are high speed (at least 20 Hz) photometric observation of blue stars on the ecliptic. In addition to using appropriate dual photometer and computing technology, it is important to choose target stars with care and carry out observations in good conditions using a well-defined methodology. Initial focus on observing predicted occultations by known EKBOs will yield information that could lead to the development of software detection algorithms to recognize serendipitous occultations by EKBOs.

If developed further, dual band high speed photometry could play a role in many aspects of Solar System research and astrophysics. Areas of research that would lend themselves to these techniques include further observation of the EKB, investigation of the Rossiter-McLaughlin effect in exoplanet detection (Ohta, et al., 2005), exploration of potential bodies in the inner Oort Cloud, and topics in astrophysics.

4. Observations of simultaneous imaging and recorded seeing provides a new method to determine limiting magnitude.

A 5 year survey of determining limiting magnitude LM included both Differential Image Motion Monitor (DIMM) measurements and SNR values in each survey frame from the 0.9m telescope. This method may be particularly beneficial to surveys of the outer Solar System in which detections rely on human eye blink comparison to identify object movement between stacked frames. The method determines limiting magnitude with an improved result that normally is undervalued in existing surveys.

Photo taken of Galaxy NGC 4725 with the 0.9m telescope

© 2019 Kingsland Observatory all rights reserved